Abstract

This paper examines how students respond when university degrees become shorter, exploiting Portugal’s Bologna Process implementation as a natural experiment. Using a regression discontinuity design based on cohort age at implementation, I find that the reform increased university attainment by 1.5pp and average schooling by 0.25-0.33 years. Students shifted away from healthcare programs—where Bologna uniquely lengthened degrees—toward STEM and economics fields, with effects concentrated among females. To capture welfare impacts, I track cumulative earnings by age, which integrates both timing effects (when people enter the labor market) and human capital effects (what they earn). While cumulative earnings are initially negative through the mid-twenties due to foregone wages as more students pursue university, they turn positive by the early thirties. Treated workers experience steeper early-career wage growth and increased sorting into higher-paying firms, particularly among females who shifted into higher-return fields. I show that 24% of the wage increase operates through the workplace channel, whereas 66% is associated exclusively to the individual. Overall, gains from expanding university access and reallocating students toward higher-paying fields outweigh losses from degree compression, validating the ’’less is more” outcome policymakers intended.

Question and contribution

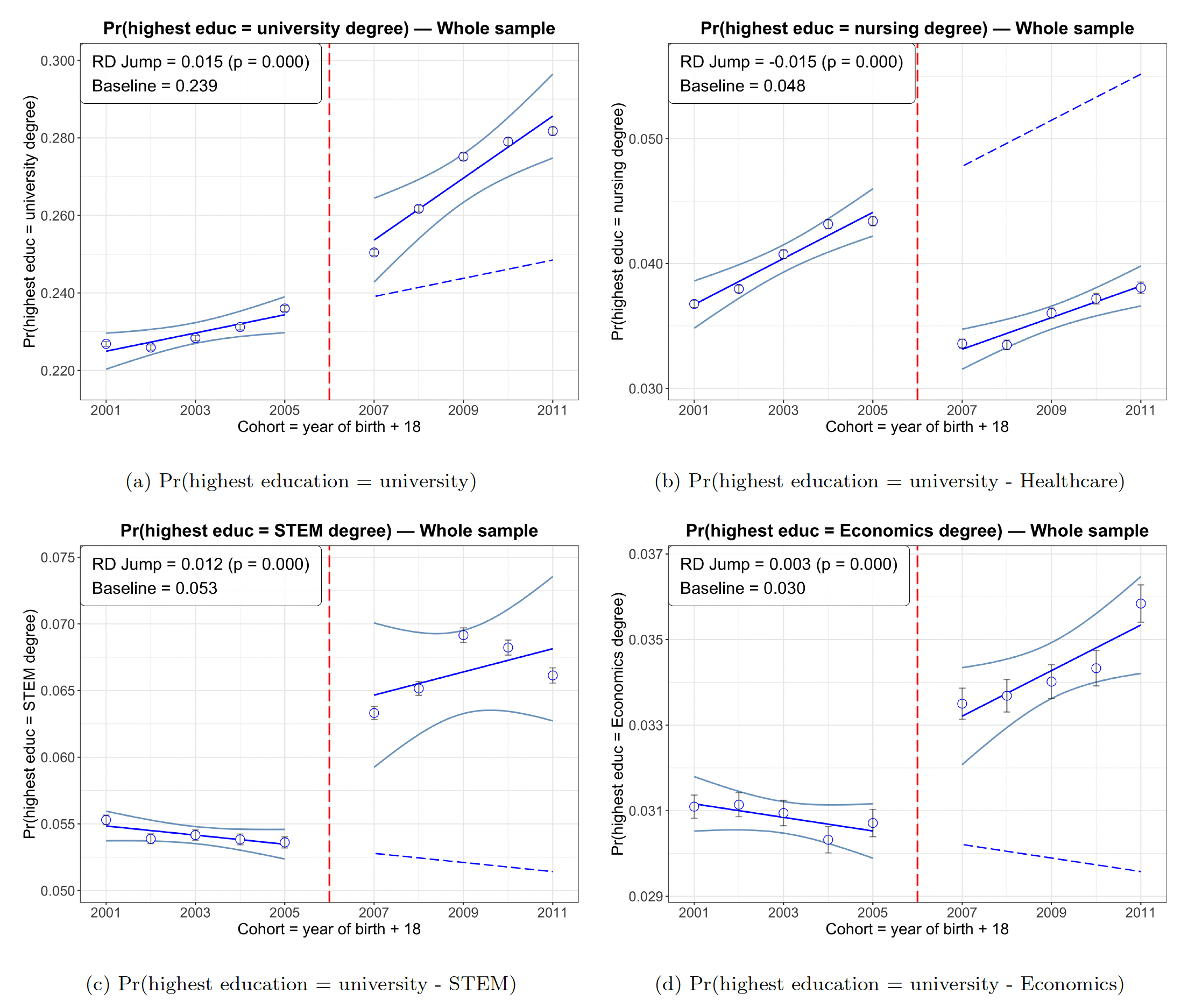

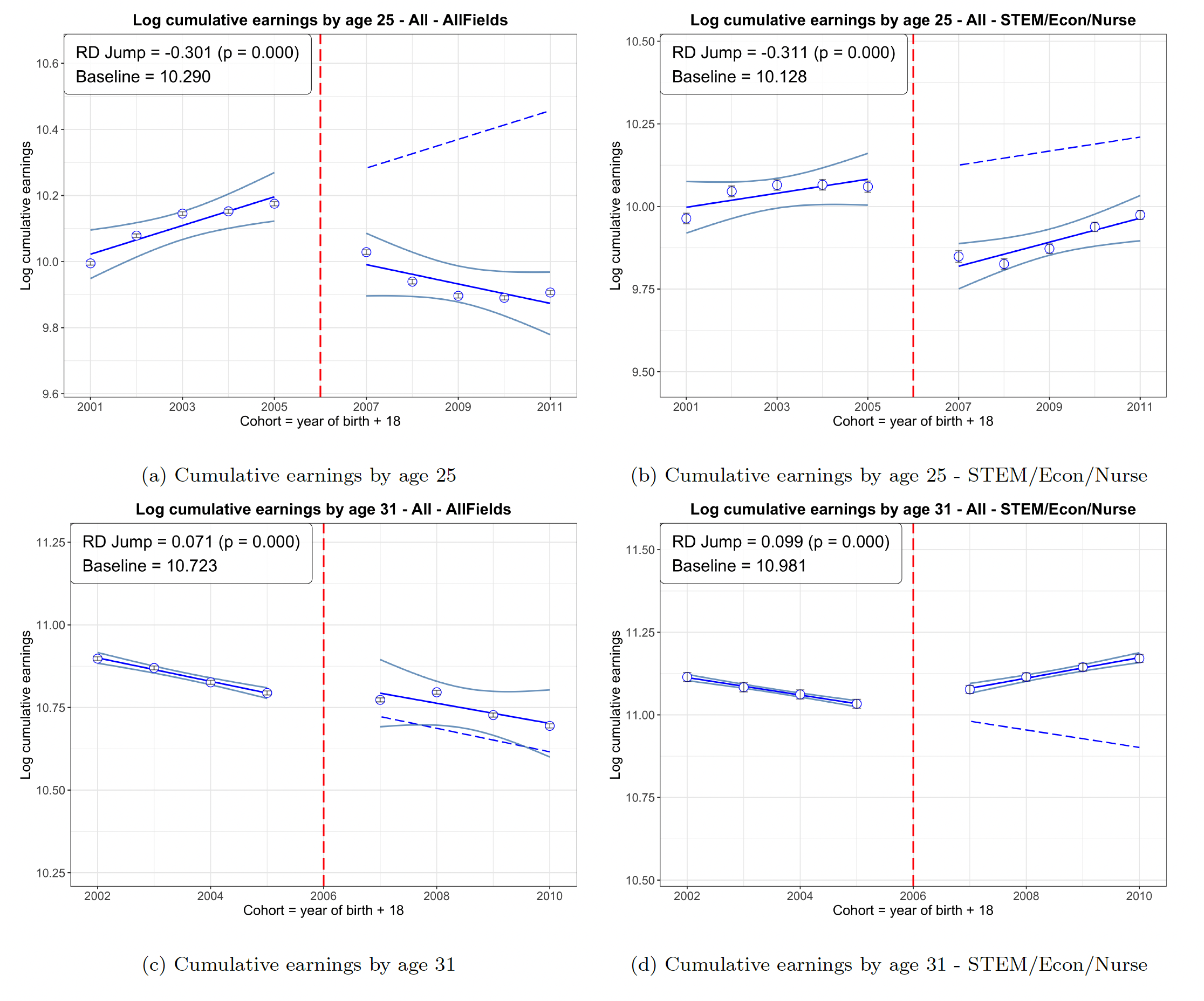

When university degrees are shortened, do the gains from attracting more people into university and more demanding but higher-paying fields outweigh the losses from compressing training into less time? I answer this by exploiting Portugal’s implementation of the Bologna Process, which reduced most first-cycle degrees from 4–5 to 3 years. This paper provides the first comprehensive evidence on how shortening degree length affects: (i) educational attainment and years of schooling, (ii) fields of study, (iii) early-career earnings, and (iv) wage formation via worker quality versus firm sorting. Although this reform affected most continental European countries, there is surprisingly little evidence on its impact beyond enrolment effects. This paper fills that gap. I find that university attainment increases, and average schooling rises by 0.25–0.33 years. Field composition shifts markedly: graduates from Healthcare decline by 30%, while STEM increases by 22% and Economics by 10%. Cumulative earnings are higher by the early thirties, and relative hourly wages rise by 3.8%. Effects are consistently stronger for women, who experience faster wage growth in the first years of employment and are more likely to move to higher-paying firms. These findings complement the literature on policies that extend compulsory schooling and on heterogeneous college returns by field of study by examining a reform that reduces time-to-degree in higher education.

Motivation and relevance

The net effect of shorter degrees on educational attainment and earnings is theoretically ambiguous because the reform simultaneously shifts two margins that work in opposite directions. On the extensive margin, shorter degrees lower barriers to university entry: students who previously found a 4- to 5-year commitment too costly might now enroll in the more accessible 3-year program. These marginal students gain access to higher-paying jobs requiring university credentials, but must delay labour-market entry and forego earnings while studying. On the intensive margin, the reform creates an earlier exit option: students who would have completed 4-5 years under the old system might now stop after 3 years with a bachelor’s degree. These students enter the labour market sooner and accumulate more work experience by any given age, but potentially sacrifice human capital from the foregone years of education. Which effect dominates—and thus whether shorter degrees increase or decrease total years of schooling and earnings on net—is an empirical question that speaks directly to the optimal design of higher education systems.

Setting and identification

Portugal’s transition to the Bologna structure was remarkably sharp: all programs were restructured within two academic years, 2006 and 2007. With a standard university entry age of 18, cohorts turning 18 in 2007 or later faced the new system, generating a cohort-based discontinuity in reform exposure at the time of university enrollment decisions. I estimate a donut RD specification around the 2007 cohort cutoff (excluding the 2006 cohort) with linear trends on either side. Manipulation tests show no discontinuity in the birth-cohort density at the cutoff, and I find no evidence of strategic delay into university around the reform (share of individuals working between high school and university remains unchanged).

Data

The analysis uses Quadros de Pessoal (QP), a universal private-sector linked employer–employee panel (2000–2023), with detailed wages, hours, occupation, education (level and field), and firm characteristics. Hourly wages are constructed from monthly compensation and deflated to 2010 euros. To control for time-specific trends, I index hourly wages by hourly wages of older, unaffected cohorts observed in the same calendar year. Additionally, I create a cumulative earnings variable

that captures both timing effects (delayed entry for new university students versus earlier entry for those who before completed longer degrees and now complete shorter degrees) and human capital effects (gains from more education versus potential losses from compression), providing a welfare-relevant measure that integrates all mechanisms through which the reform operates. To benchmark selection, I complement QP with nationally representative Labor Force Survey (LFS) microdata representative of the whole population.

Main findings

The reform raised university attainment by 1.5 pp in QP and 1.8 pp in LFS (baseline 23.6% and 18.0%), with the first-cycle (bachelor) margin accounting for most of the increase. Proxies for schooling indicate a net rise of roughly 0.25–0.33 years (LFS age at completion +0.254; QP age at labour-market entry +0.327). In both QP and LFS samples, effects are stronger for women. Healthcare (excluding medicine) completion—the only program that became longer under Bologna—declined by 1.5 pp (31% relative to baseline), while STEM rose by 1.2 pp (22%), and Economics by 0.3 pp (10%). These shifts are, again, concentrated among women, and validated using the LFS sample.

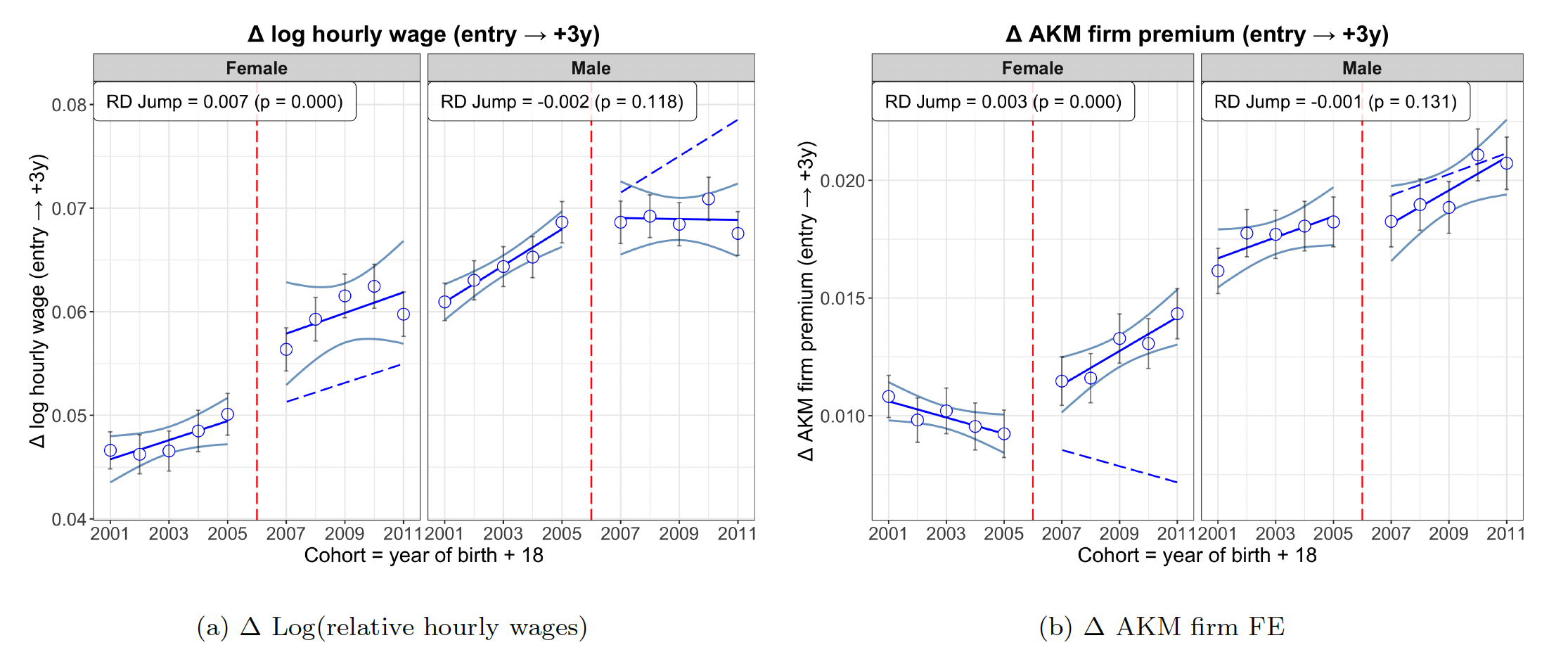

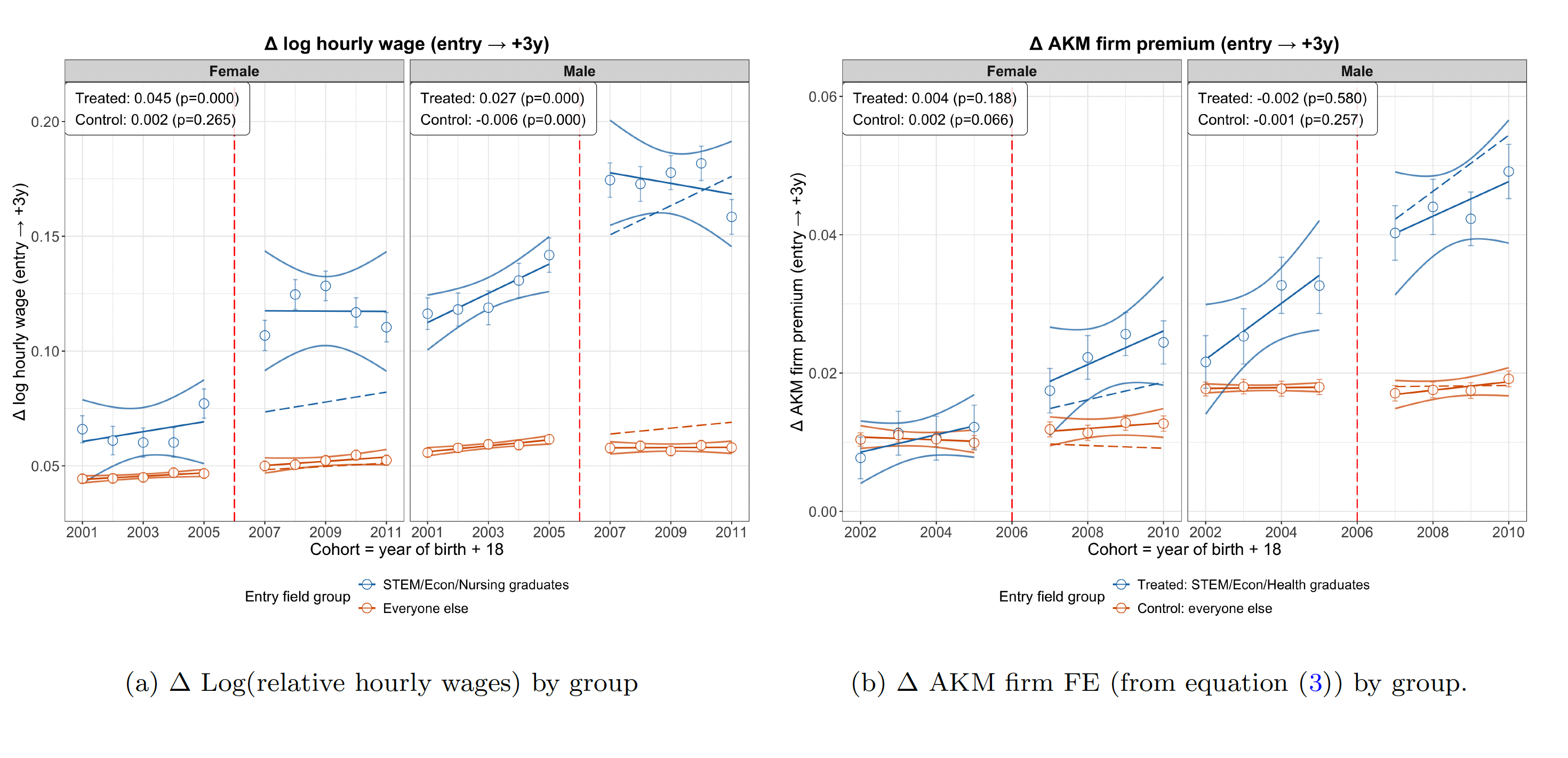

Relative hourly wages rise by 3.8% at the cutoff (4.2% for women; 3.3% for men). Back-of-the-envelope calculations using the schooling proxies imply returns per additional year of education in the 10–15% range. A decomposition using an AKM model with individual, firm, and occupation effects shows that 66% of the wage gain is an individual component purged of sorting, 24% operates through firm sorting, while the occupation component is negligible. Cumulative earnings are lower in the mid-20s, highlighting foregone earnings as more students study, but turn positive by the early 30s.

Patterns are similar by gender, yet women catch up through faster growth. Post-reform women are more likely to transition into higher-paying firms in the first years after graduation and exhibit steeper early-career wage growth.

These mobility and growth effects are driven by individuals graduating in Healthcare, STEM, and Economics, indicating that the positive impacts of degree shortening are partly composition driven: the reform reallocates students toward fields of study that offer steeper wage ladders, i.e. toward STEM and Economics and away from Healthcare.

Robustness

Education results are robust across QP and LFS samples (addressing private-sector selection), to alternative bandwidths in the RD, to indexing wages by calendar-year–gender cells, and to “donut” exclusion around the cutoff.

Implications

Compressing degree length expanded access, shifted students—especially women—toward higher-return fields, and raised early-career wages mostly via improved worker quality, with a meaningful contribution from improved firm sorting. Although there are transitional earnings losses in the mid-20s, net effects turn positive by the early 30s, as measured by cumulative earnings. On balance, Portugal’s Bologna reform delivers a ’’less-is-more” outcome: gains from access and reallocation across fields dominate potential losses from curricular compression.